| • CONTACT |

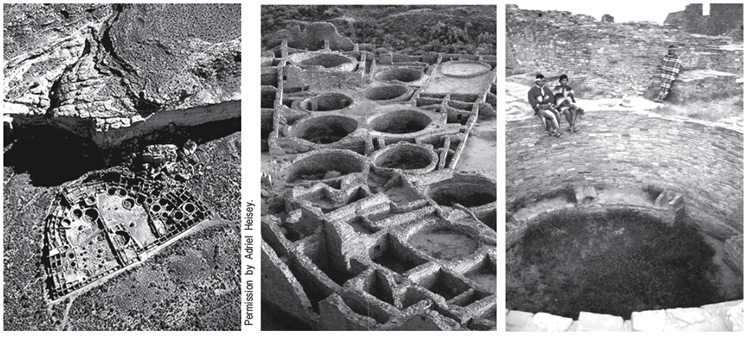

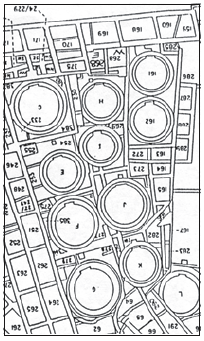

Pueblo Bonito (Above and Below)

| Granary Row Styles of aquimé/Chaco-Pueblo Bonito Kiva Silos |

|

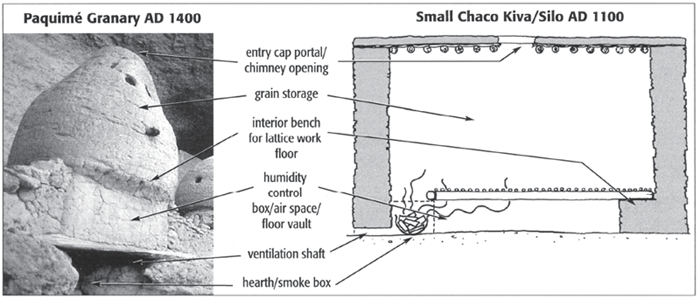

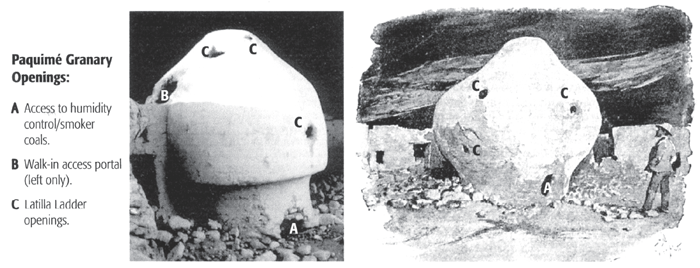

The archaeological debate whether the smaller kivas at Chaco (C.E. 850 - 1130) were actually corn storage silos continues. In the Paquimé (C.E. 1250 -1425) culture region, however, the silos or granaries are self-evident. Corn must be stored at 12 percent or less moisture content or it will mold. Silo (kiva) “benches” and horizontal wood beam pilasters, like those found in Chaco Canyon N.M. kivas, may have supported a latticework floor with an air space beneath to keep the corn dry (bottom right). The space for the horizontal wood beam pilasters are clearly visible on the exterior of the Paquimé granary (top right). In both cases, these extensive and large granaries indicate corn was widely grown throughout the region and then centralized for storage. In the Paquimé culture region the corn was dried, stored and then transported to Paquimé itself, approximately 75 miles from the Sky Island site. At Chaco, the corn was grown up to 75 -100 miles away, transported to the central outliers, and then transported again for storage in Chaco Canyon villages such as Pueblo Bonito. Transhumance agriculture is strongly supported by the evidence in this unique architecture. The collection of fertile water and the corn storage strategy gave the Anasazi and Paquimé peoples the ability to survive many short-term and a number of severe long-term droughts (above).

Technology of Paquimé/Chaco Smoker Granaries-Kiva

Silos Based on our research of Paquimé granaries, I believe that the smaller Chaco kivas should be re-evaluated as multipurpose facilities that were primarily used as silos and, when empty, were also used as living quarters previous to abandonment and for religious blessing ceremonies after C.E. 1275. Many archaeologists agree with the living quarters theory, but fail to explain the hearth and ventilation system that produces carbon monoxide built into the smaller “kivas.” Our research indicates a completely new theory that explains the hearth and ventilation features. What I propose is that these Chaco silos were such high tech grain storage facilities that most archaeologists have not as yet accepted any theory as to their practical use as long-term grain silos. As excavated by Emil Haury, the Hohokam had a less well understood structure that had a raised floor, fire pit and schist stone risers and may have functioned in the same way as kiva silos and olla granaries. Although burials are common in Hohokam pit houses, there is no burial documented in this room. My original proposal, based on a study of the Paquimé granaries, is that the Anasazi used live coals in the hearth below the humidity control box to manage environmental conditions in the storage chamber above. The smoke and tannins released from the charcoal helped flavor, preserve and protect the stored grain from mold, insect and rodent pests. Robert M. Adams, the archaeologist who proposed this very ingenious theory, also observes that carbon monoxide from a sealed chamber is a very effective pesticide that has no harmful effect on grain as a food product. Kivas, however, are very dangerous to humans who might be using these small, dark and smoky chambers as emergency living quarters. This storage strategy helped the Anasazi and Paquimé peoples survive many droughts and contra-indicates living quarters and religious chambers. It is important that there are no burials in the round rooms of Pueblo Bonito, said Roger Moore, an archaeologist at Chaco Culture Park. It is also significant that there are no burials in Granary Row at Pumpkin Center or School House Point. It is clear that these peoples avoided burials in food storage facilities. Burials are not associated with Granary Row at Pueblo Bonito or Salado granaries, further supporting our hypothesis for long-term food storage.

|